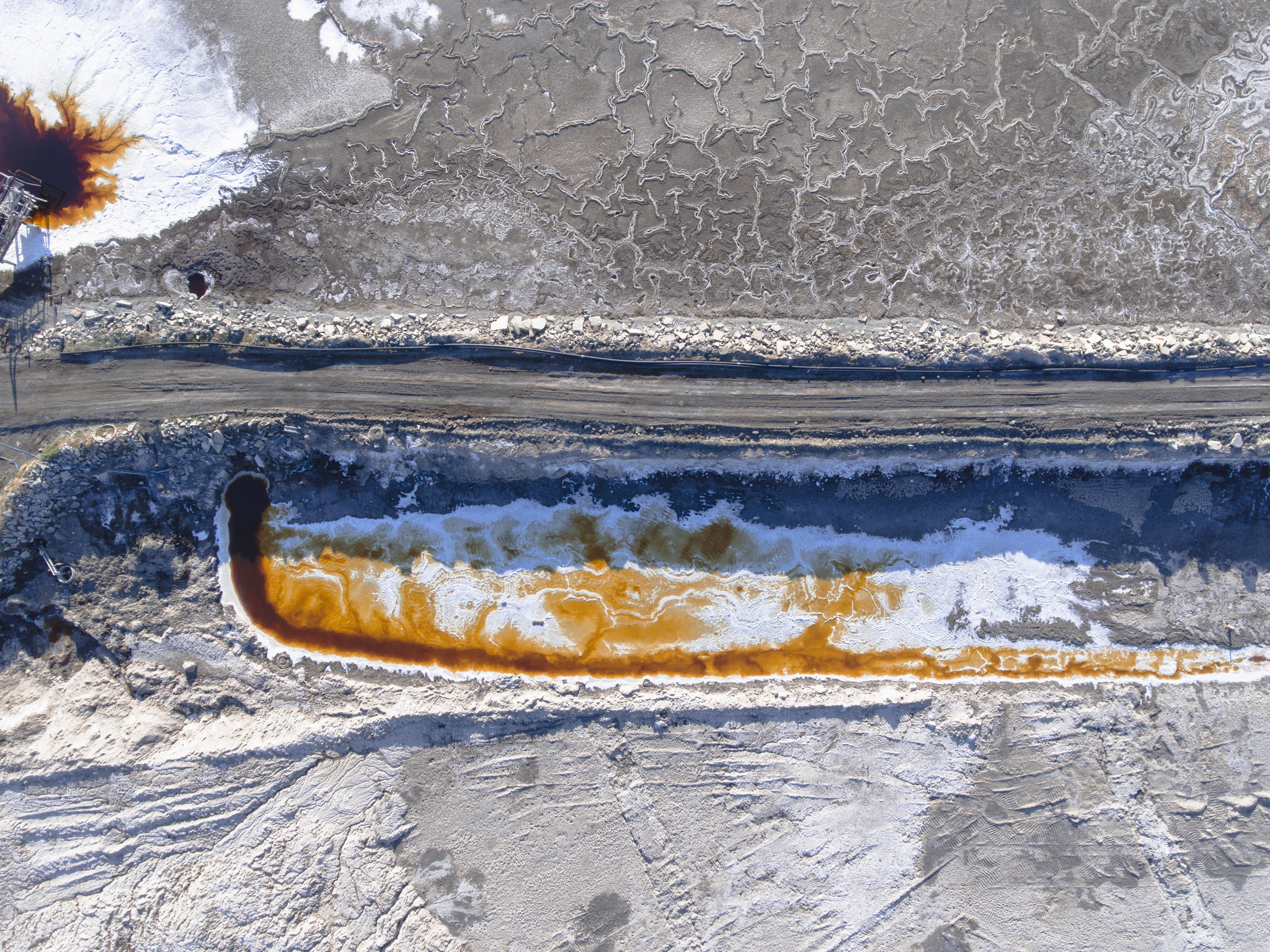

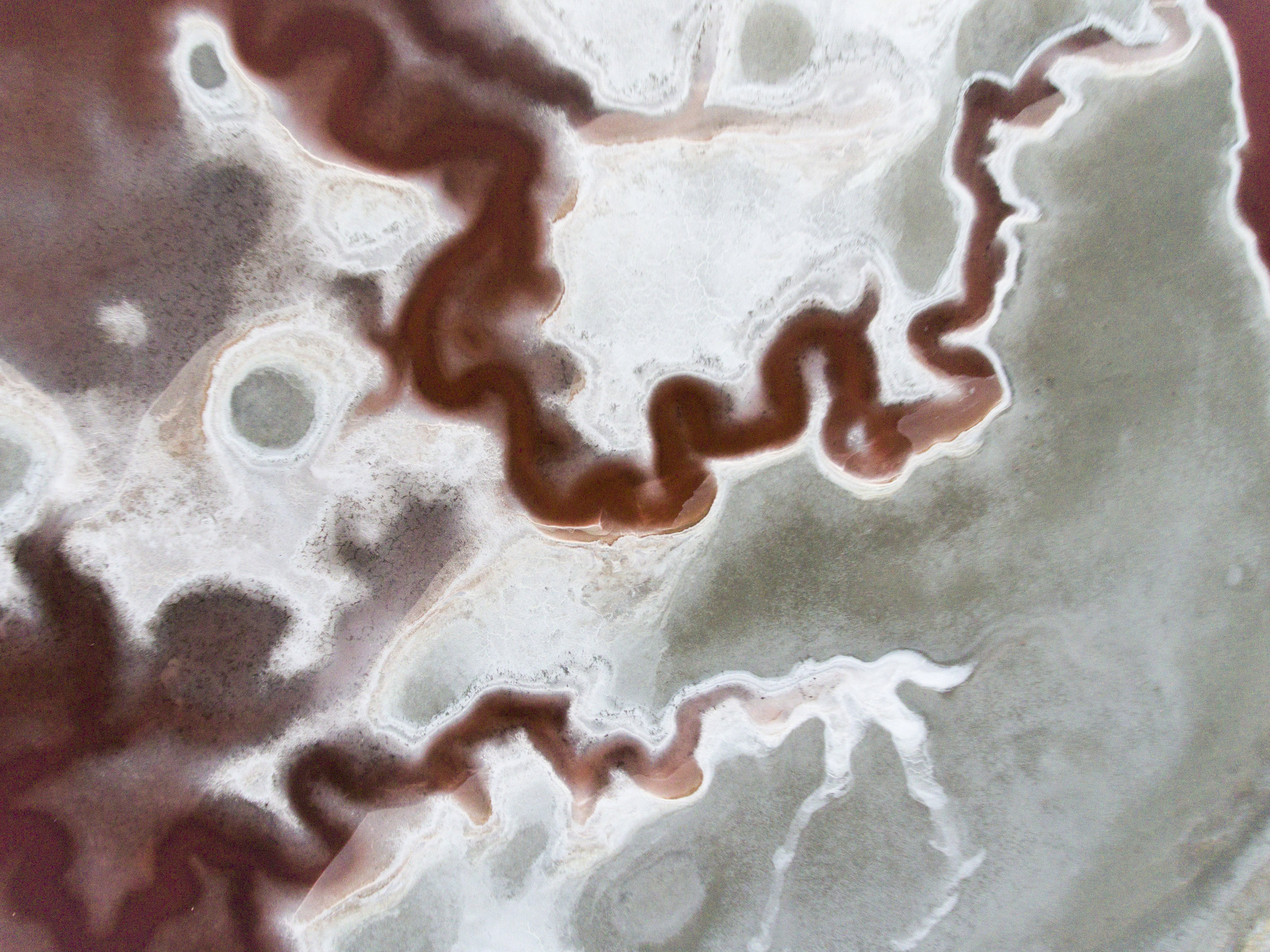

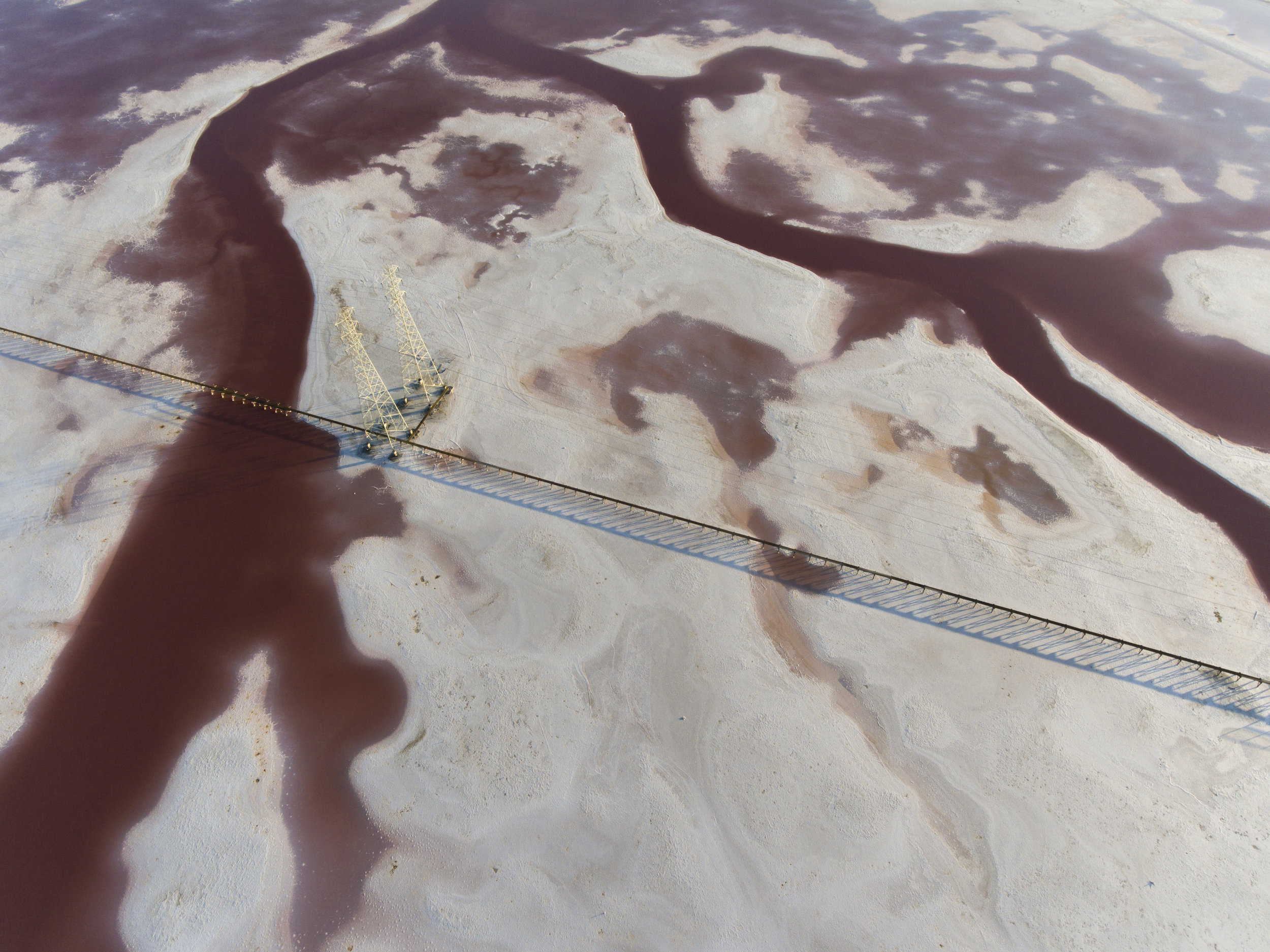

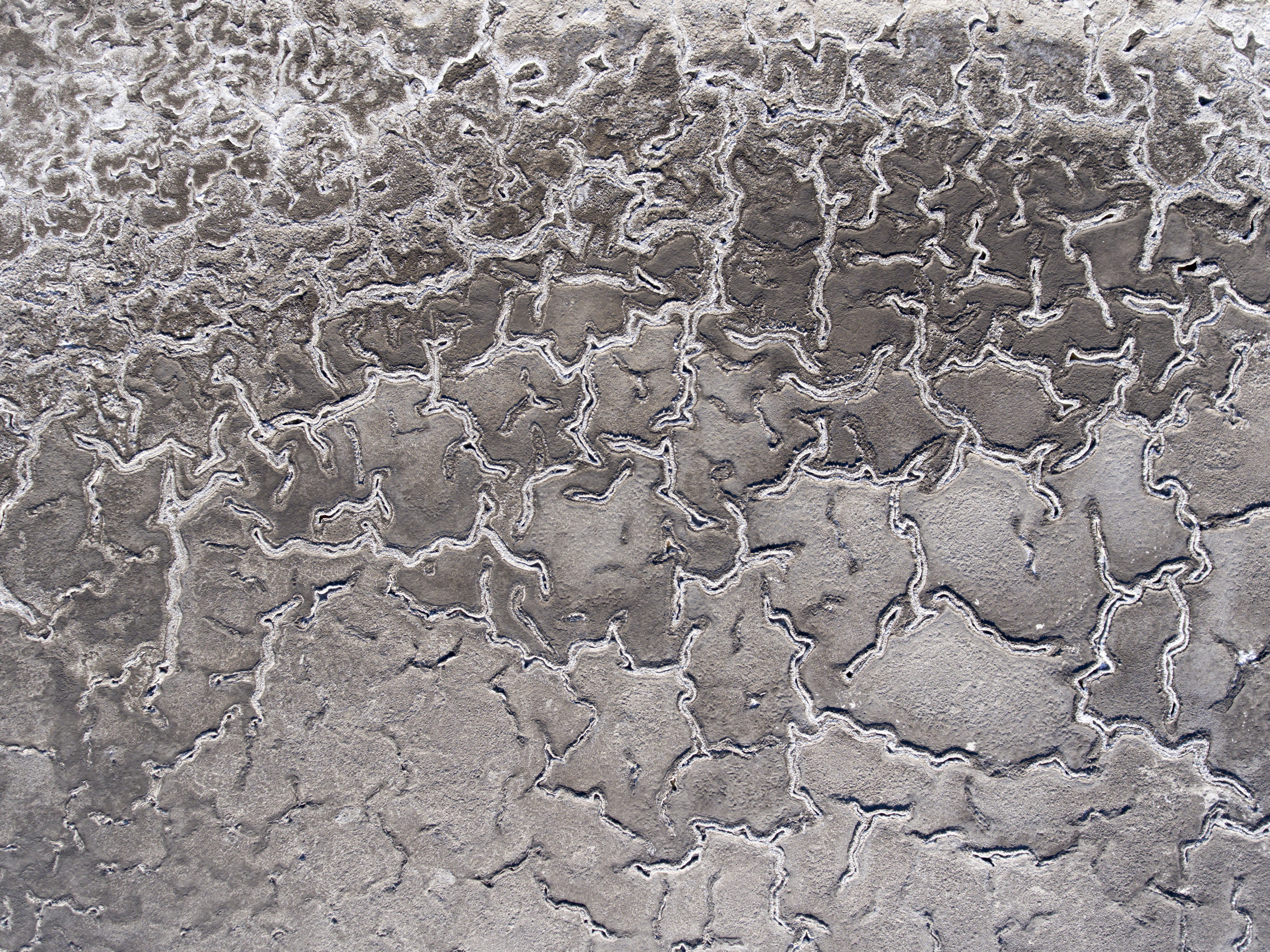

A peculiar area stands out when viewing the San Francisco Bay’s coast by plane or satellite. An arrangement of striking reds and oranges pierces through the blues and greens of this California landscape that is sure to surprise those accustomed to the state’s picturesque mountains and beaches. However, this area is as much Californian as is anything else. These vibrant colors are a product of a 150-year-old salt industry—beginning during the Gold Rush—that has converted thousands of acres of the San Francisco Bay’s wetlands into evaporation pools and has allowed a community to settle on its shores (Sommer).

However, in the past two decades Cargill, one of the largest agricultural corporations in the world, has begun donating large areas of their operation to the government and environmental preservation groups, and for good reason (Cargill). Salt evaporation ponds are only advantageous for salt production purposes and offer few environmental benefits. Tidal marshlands once spanned a large portion of the San Francisco Bay’s shoreline—the second largest estuary in the United States—but now over 80% of them have been modified for other purposes (South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project, Wood & Pitkin). This valued ecosystem is effective at absorbing floodwater, acts as a buffer against storm tides, provides a healthy habitat for many species of wildlife, and is better suited for adapting to sea level rise (Wood & Pitkin, EPA). Climate change threatens to intensify these processes, leaving shorelines comprised of salt evaporation pools especially vulnerable.

The South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project, the group in charge of leading this conversion effort, is determined to fortify the Bay’s coast against these consequences. Since their acquisition of 15,100 acres of salt ponds from Cargill in 2003 this team of biologists, engineers, and project managers have been nobly restoring the Bay’s shoreline back to tidal wetland (South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project). This enterprise will generate numerous benefits for local communities, among which will be the prevention of tens of thousands of people and critical business real estate from being displaced by sea level rise (Vital Signs). In a fascinating instance of karma, one of the region’s most historically profitable industries of salt production is now threatening the Bay Area’s new economic powerhouse of Silicon Valley.

Despite this progress, Cargill continues to operate at one site by Newark’s coast. It endures as the last area in the San Francisco Bay to display the incredible patterns and colors associated with salt production. However, the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project’s larger goal is to restore a total of 40,000 acres back into tidal marshland, implying that this last surviving area may soon perish (South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project).

****************

This photo project serves as both an exploration and record of this fascinating part of the San Francisco Bay’s history before it disappears altogether. In the near future Newark’s shoreline will visually mimic its neighboring tidal marshlands that have already been restored. Only certain types of bacteria can survive the high salinity in these ponds, producing their prominent colors. It is a unique occurrence in which an anthropogenically transformed environment has resulted in a habitat that allows a single species to thrive, which, in turn, drastically alters the landscape’s appearance on its own. The Bay will soon bear some semblance of its former self, dominated by deep colors of green and blue. Although converting this stretch of coast back into tidal marshland is undeniably important, it does mean that these accidental, human-made landscapes—with all its vibrant hues and intricate patterns—are going to disappear forever. Currently the vast majority of images taken of this area come from plane windows or satellites, but neither of these sources effectively display the wonder and detail of these salt evaporation ponds. It’s important for more photographers to capture these transient and perversely beautiful landscapes as more companies follow Cargill’s lead and begin to return transformed and altered areas to their original states.

Observation of this landscape is—to a certain degree—inaccessible to the public because of its location in the water and its size. Thus only an aerial vantage point can offer an adequate experience. All images for this project were taken with drone flown between 40 and 120 meters above ground and employ a mixture of vertical and oblique perspectives. To appropriately illustrate these anthropogenic transformations in an impartial manner these photos utilize a deadpan approach, wherein the images are intentionally devoid of emotional manipulation or personal interpretation. Ideally this project encourages more people to recognize the unique beauty of these salt ponds in the San Francisco Bay before they fade forever, and—at a larger scale—to think about the visual implications of humans altering Earth’s landscapes, whether by degradation or restoration.

****************

Sources:

Cargill. “San Francisco Bay Salt Ponds.” Cargill. Accessed: June 3, 3019. https://www.cargill.com/page/sf/sf-bay-salt-ponds

EPA. “Classification and Types of Wetlands.” EPA. Last modified: July 5, 2018. Accessed: June 3, 2019.

https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/classification-and-types-wetlands#marshes

Sommer, Lauren. “What Are Those Weird, Pink Ponds in San Francisco Bay?” KQED. Published: December 14, 2017. Accessed: June 1, 2019.

https://www.kqed.org/science/1918301/what-are-those-weird-pink-ponds-in-san-francisco-bay

South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. “Project Description.” South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. Accessed: June 1, 2019.

http://www.southbayrestoration.org/Project_Description.html

Vital Signs. “Vulnerability to Sea Level Rise.” Vital Signs. Accessed: June 2, 2019.

http://www.vitalsigns.mtc.ca.gov/vulnerability-sea-level-rise

Wood, Julian and & Pitkin. “Saving Tidal Marshes in the San Francisco Bay.” Point Blue Conservation Science. Last modified: January 17, 2017. Accessed: June 2, 2019.

https://toolkit.climate.gov/case-studies/saving-tidal-marshes-san-francisco-bay